“When feminism does not explicitly oppose racism, and when antiracism does not incorporate opposition to patriarchy, race and gender politics often end up being antagonistic to each other and both interests lose.”

–Kimberlé Crenshaw, “Whose Story Is It Anyway? Feminist and Antiracist Appropriations of Anita Hill,” 1992

Throughout the hardships and obstacles the world throws at Black communities and especially Black women, where do we find the joy? Upon writing this article, this was a question I pondered daily. Hands Up is comprised of seven monologues that detail Black Americans’ experiences with police in America. The monologue – “Dead of Night,” written by Nambi E. Kelley – details the specific experience of being Black and a woman while dealing with police brutality. In reading this monologue, I started to think about the in(visibility) of Black Women in the movement against the racial discrimination of Black people. Black Women are constantly caught between the space of having to choose if they are Black or Woman first, which can ultimately put them in second-class positions for both experiences.

This experience is not unfamiliar to playwright Nambi E. Kelley. In a conversation with her about Hands Up, she discussed that during her time as an undergraduate, she didn’t experience a place of freedom. Kelley's work is influenced by the likes of Ntozake Shange, and many of her professors were puzzled by how to critique her work. As this can be frustrating for many students, Kelley decided to use this as motivation to know that she was creating work that highlights a specific lived experience, the Black experience. She didn’t let this destroy her love for writing or her confidence. Kelley demanded the visibility of work in a world that insists on Black Women’s in(visibility). We see the power of her voice continue throughout her work on Hands Up.

Initially, Hands Up consisted of six monologues by six different playwrights. Later, Keith Josef Adkins contacted Kelley, wanting to add a woman’s voice to the narrative. She recalls, “Sandra Bland happened. … Adkins, the curator of the series, emailed me and said he wanted to add a lady’s voice to the piece and asked if I had something to say.” This moment was the birth of “Dead of Night.”

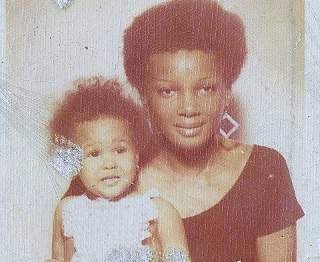

Though the weight of this play is palpable, in conversation, Kelley and I pondered the question again: Where do we find the joy? It’s a question I’m sure many Black Americans ask themselves after constantly dealing with racial trauma every day. The one way we can experience joy is in knowing that we are continuing the legacy of strong Black men and women who grace this earth. When asking Kelley who inspires her, she quickly responded that it was her mother. Her mother knew that the joy in life was in living. “She didn’t waste her time in what was taken from her. She focused on living. My mother was a brilliant woman because she lived.” She goes on to say, “I’m glad to turn my pain to champagne. It’s my liberation. If you get something out of it, cool, but I freed myself.”

The greatest act of rebellion Black Americans can participate in is to live life to the fullest every day, regardless of whether or not someone tries to strip us of those moments. Hands Up, while highlighting Black struggles with police brutality, demands contemplative action from the reader and the watcher. Perhaps we all, through this piece, can find moments to turn our pain into champagne.

Please note: "pain to champagne" is a phrase borrowed from Nambi's partner, Daniel Carlton.