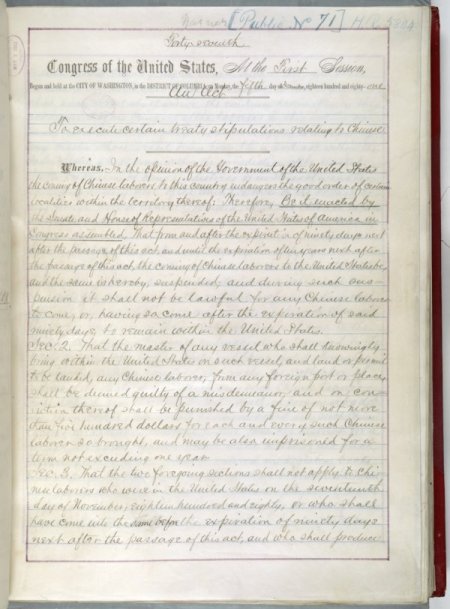

An act to execute certain treaty stipulations relating to the Chinese, May 6, 1882; Enrolled Acts and Resolutions of Congress, 1789-1996; General Records of the United States Government; Record Group 11; National Archives Large

In the early to mid-19th century, gold was discovered in California, the railroad industry was booming, and Great Britain's illegal exportation of opium into China soon led to the Opium Wars. These conflicts, famine, and destabilization severely impacted China’s economy, particularly in the Guangdong region, where Afong Moy was born. Many Chinese laborers left their home to find work in the burgeoning industries of the American West. American companies, prohibited from using enslaved labor in the Free territories, exploited Chinese immigrants by offering low wages and imposing long work days.

Chinese immigrants faced pervasive xenophobia, racist articles, and propaganda depicting Chinese immigrant communities as unclean, drug-addicted, or otherwise threats to American values. In 1854, the California Supreme Court case People v. Hall ruled that testimony from Chinese people against the White people was inadmissible. The ruling held that Chinese people were “a race of people whom nature has marked as inferior.” This decision effectively legalized violence against Chinese Americans, resulting in a surge of under-legislated hate crimes.

Racism and xenophobia exploded into the LA Chinatown Massacre of 1871, triggered when a police officer was wounded and a saloon owner died during a shootout between two rival Chinese criminal organizations. During the massacre, a mostly White mob lynched nearly 10% of the Chinese American population in Los Angeles. All convictions brought against the mob were overturned on technicalities. A few years later, The Page Act banned the importation of forced laborers and sex workers from any nation in Asia; its enforcement relied on the sexualization and fetishization of Asian women. The Page Act was enforced in a way that aligned all Chinese women with sex work, and immigration officials were given full authority to bar Chinese women from entering the United States. In 1877, the Workingmen’s Party of California, a racist labor organization, was founded with the goal of eradicating Chinese laborers from America, espousing the slogan, “the Chinese must go.”

In 1882, the United States passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, the first immigration bill to explicitly ban a specific race or nationality. This act banned all Chinese people from entering America with few exceptions.

During the Exclusion era, the nearly 110,000 Chinese Americans who immigrated before 1882 were denied naturalization, barred from owning land, and prohibited from interracial relationships.

In 1885, a White mob razed the Chinatown in Rock Springs, Wyoming, forcing over 600 Chinese residents to flee and killing at least 28, though the actual number of deaths may have been higher. The 1887 Hell’s Canyon Massacre resulted in the deaths of 34 Chinese gold miners. The site was renamed “Chinese Massacre Cove,” and the memorial sign reads: “No one was held accountable.”

The Chinese Exclusion Act was not repealed until 1943; even then, only 105 visas per year were given to Chinese immigrants. It wasn’t until 1965 that the quota was increased to 20,000. The legacy of Exclusion-era policies and racist rhetoric continues to affect Chinese Americans today. Hate crimes against Asian Americans increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, fueled by the same stereotypes that led to the Chinese Exclusion Act. In 2021, the Atlanta Spa Shootings were a targeted attack against Asian women, the tragedy connected to the dehumanization and sexualization of Asian women that resulted in the Page Act of 1875.

Right now. Right here. In 2024, it is our responsibility to listen to the voices of Asian Americans, amplifying them over the harmful narratives and tropes that originated in the Exclusion era and undoing the legacy of harm caused by the enactment of the Chinese Exclusion Act.

Special thanks to Tom Zhang, Visiting Assistant Professor at the University of Kansas, theater-maker, actor, and one third of the Atlanta Theater Collective You Should Feel Bad for their consultation on this article. Tom is dedicated to creating performances that use humor to explore race relations and American identity. You can learn more about their work at thetomzhang.com.

Performances of The Chinese Lady will take place on the Hertz Stage, September 18 – October 13, 2024.