Hahnji Jang – Costume Designer and Cultural Consultant for The Chinese Lady

One of my favorite aspects of costuming is the chance to give depth and meaning to a figure in history we know very little about but is significant to a community. For The Chinese Lady, I was excited to explore who “Afong Moy” could be since we know very little beyond her function of highlighting the use of Chinese merchandise for the Carney Brothers and later as an “act” for the Barnum Circus. Similarly, “Atung” was an even larger mystery to me than Afong Moy whose origin was better recorded in the advertisements for her “show.” After exhausting this documentation of Afong Moy and Atung, I decided to explore the character’s backstories further by questioning their path to this room.

For Afong, we knew that she was one of many daughters sold by her parents to American merchants to demonstrate the new Chinese fine goods being sold in the USA. My question was always, why her? For a possible backstory I turned to one of my favorite resources, “Making Queer History” (MQH). MQH publishes articles about queer figures and events from around the globe, organizing them by country with the goal of highlighting the queer culture that existed pre-western colonization and continues to exist despite attempts to eradicate it in the pursuit of global capitalization. I read an article about the Golden Orchid Society, a society of women in China who rejected heterosexual arranged marriages in favor of entering into marriages with other women, which their families now had to accept due to the silk industry boom raising a woman’s potential earnings. I was drawn to this fact as the same silk granting independence to these women is the same silk that Afong is in America to demonstrate for the crowds that come to see her. This silk trade ultimately became so popular that today, almost a century later, we are able to use secondhand silk remnants available to create the Afong Moy costume.

The Golden Orchid Society wasn’t only for same gender marriage but also included women who “married themselves” in ceremonies, referred to as “self-combing women.” A middle part in the hair signified an unmarried status in this period, only to be combed back once married. This rare visible inclusion of the asexual/aromantic community also intrigued me as I wanted to ensure that Afong Moy was not sexualized as an Asian Woman and seemingly instead married to her purpose to expand the American understanding of the Chinese woman beyond stereotypes.

1800s Cigarette Card From the NYPL Picture Collection

In intensifying the contrast of the moment she is being the most objectified in the play, her costume reflects depictions of Chinese women from western cigarette cards. This look removes her autonomy as it covers her hands and features a large elaborate wig, hair ornaments, and makeup — weighing her down unlike the possibilities a "self-combing" woman could have. As one of our few appearance aspects we can alter by choice, hair is often deeply personal and full of cultural coding options. This carries into Atung’s costume design as well.

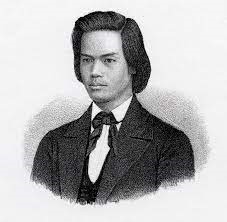

As I researched how Atung could possibly have reached this room, I found historical notes of Yung Wing and other Chinese young men brought back by Christian missionaries to attend universities.

Yung Wing Portrait from Yale University

Naturally I began to imagine Atung as one of these students, strengthening his passable English at an American University. I loved that the renderings available of Yung Wing featured longer hair, possibly hinting at a streak of rebellion (as hair often is holds for queer folks), with further subtle commentary against the traditionally enforced Chinese long braided queue, or maybe it was against Western standards and the missionaries who had cut his hair short. Either way it was one of two main ways I was able to understand and queer code Atung with the other being the symbol of the bitten peach.

There is also a story in ancient Chinese literature, Han Feizi, centered on the peach - 餘桃啗君 (feeding emperor with the bitten peach). In the Zhou dynasty (771–256 BC), Mizi Xia was famous for his impeccable beauty and was the favourite same-sex courtesan of the state-ruler, Duke Ling of Wei. One day, when they wandered through the garden together, Xia picked a peach and took a small bite. As soon as he realized how particularly sweet the peach was, he handed the remainder of the bitten peach to the Duke. The behaviour could have been seen as a significant disrespect to the royal ruler. However, Ling of Wei took the bitten peach and instead praised Xia’s sincere love. The symbol of the bitten peach (餘桃) is still a coded phrase for romantic relationships between men in China. – Asian Arts and Culture Trust

Inspired by this story I chose to highlight the bitten peach through a peach shaped pocketwatch. This time piece is a key way Atung interacts with the show and has become his own small subtle way of claiming both his Chinese culture and his queerness in front of the audiences that come to see Afong Moy.

Sources

https://www.makingqueerhistory.com/articles/2016/12/20/the-golden-orchid

https://www.makingqueerhistory.com/articles/2016/12/20/the-bitten-peach-and-the-cut-sleeve

https://www.aact.community/experience/open-call-the-bitten-peach-decolonizing-queer-asians

Performances of The Chinese Lady will take place on the Hertz Stage, September 18 – October 13, 2024.